✷

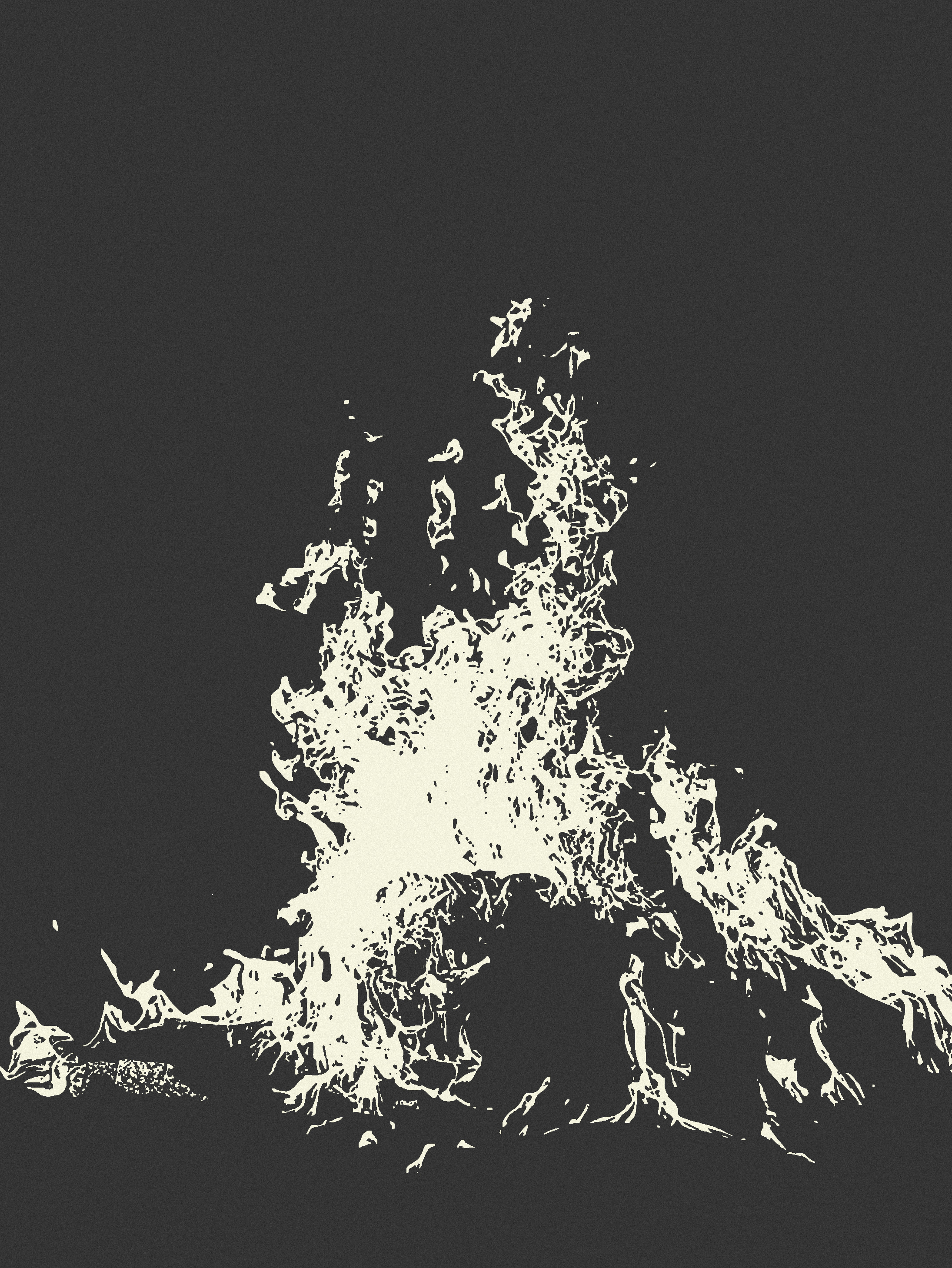

Everybody loves the woods, until they follow you home.

When my father came back from the military, we bought our first house—a boxy, two-story affair on the woodsy outskirts part of town. I was twelve, going on thirteen then.

Our neighborhood was a little off the beaten path, nestled somewhere between shaded canopy roads and miles upon miles of Tallahassee timber.

After school, if I didn’t have a scout meeting or any more chores left, I’d hop on my bike to find friends to hang out with—the only rule was to be home before the streetlights came on. Throughout all my childhood, my folks never asked where I was going or what I was doing for the day.

Times were different back then, I guess.

My summers were spent playing in the woods with my friends. It was the perfect place to turn off the world for a while, like you were miles away from any sort of responsibility. Nothing but dirt and adventure.

We played war for hours, following deer trails, bridge-jumping into freezing creeks, and always knew to get the hell out of dodge when riders blasted their way down the trails. The last of us to move always won.

Honestly speaking, we were no different from any other group of dumb kids hurting themselves for laughs and style points. Self-injury is the oldest form of amusement, after all, and for a group of skinny, bored desperados, how could we not be just a little bit reckless?

Sprained ankles, bleeding arms, and scuffed knees were all par for the course, my friend Joel once pulling a tree branch back and letting it fly straight into the face of Teddy Mare. It struck Teddy so hard his head whipped back and his lip inflated like a balloon. He lost his last baby tooth that day.

Sometimes, if we ever felt up to it, we’d make the trek to Hollow Sink Park to stare at the sinkholes that tourists came to gawk at. The park was littered with them, but we mostly went to see the Dismal Maw—at least we did until some kid drowned in it. A friend of mine once said he saw the boy’s white face staring at him from the black water. I figured he was full of shit.

I knew the woods like the back of my hand, and other than a decent escape for us, they had also become a series of shortcuts we could use to reach each other’s houses, lickety-split. Hard to get lost if you memorized landmarks and stuck to the damn trail. Neglecting that is how most poor souls ended up on the news.

✷

One evening, I was with Joel in his garage trying to complete our construction of a bike ramp for the summer. Despite the sky draining to a dense, bruised color, I stupidly let him razz me into staying just a bit longer to get more of the ramp done.

If not for the looming threat of my old man ripping me a new one, we’d probably have had it all finished, but I waved him off and rode the bike home.

I decided to cut through the woods—it was my only chance to beat the automatic circuits of the street lights that were waiting for enough light to disappear.

I followed down the path as it dipped into a creek and then smoothed out into a single-track lane.

Wet clods flew off my tires as the gears buzzed and jittered along the trail. I was still saving up for one of the fancier Rockhoppers that riders used, but until then my clunky hybrid was enough to get me around.

The sun dropped like a beacon in the distance, taking away what time I had left. I had to hurry.

I kicked it up a notch, speeding through the trees and the Spanish moss that hung from them like a hippy’s dreadlocks.

But just as I crested the brow of a hill, I suddenly had to stop.

My upper body jerked forward off the seat as I slammed on the brakes and brought myself to a crunching halt along the grit.

Ahead of me, just a yard or so away, the body of a white-tailed deer blocked the path. It was lying on its side, all four legs splayed out from under it.

The skin had been torn away from its back, leaving the pelt to sag around the exposed flesh, damp with blood. Great chunks of meat were gone, carved out by sharp teeth from whatever had killed it. Somewhere within the ragged, chewed muscle, I thought I could make out the semblance of a spine.

A fresh kill.

Predators weren’t uncommon here, but they mostly stuck to the human-free spaces of the forest. As many times as we explored this place, we very seldom ever saw them.

Something moved out of the undergrowth.

My eyes snapped toward it. My heels instinctively scraped the earth to back the bike up.

A large black hound.

It was a mangey-looking thing, romping out of the covert and toward the corpse.

A wolf, I thought, as my eyes traced the thickets for any more signs of movement. There didn’t seem to be any.

Taking no notice of me, the hound bowed its head and began to sink its teeth into the carcass, pulling and tearing off more parts.

The hound was covered in tangles of dark, scanty fur. I’d never seen a dog’s coat so black, like it was more of a dog-shaped silhouette than anything else. The same pitch as a starless night sky.

I backed away slowly, trying to raise as much distance from it and me as possible as I rotated the bike around.

A few rocks shifted and scuffed loudly under my tire—I had moved too quickly.

The hound reared its shaggy head toward me.

I stopped moving.

Its body rose up and stiffened, the sides of its dark muzzle quivering. Ropy strings of saliva dripped off its chin, falling over the remnants of what once was a deer’s jugular now gripped in its teeth. The hound was big, maybe the size of a mastiff. Maybe just a bit bigger.

But what sent the ripple of static down my spine was the single white saucer it had for an eye. Dead center, bulging outward from the animal’s head, the eye held a vague whiteness without any hint of sight.

The hound’s body lunged forward just as I twisted around and started beating the pedals.

I went full throttle, riding the downhill burst at a neck-breaking speed.

It’s not after you, I told myself. It just wants you away from the deer. It doesn’t want you.

But it was coming. I knew it was.

My bike wavered wildly back and forth along the rugged earth. I was standing up, pumping the pedals madly and forcing the handlebars still.

Against every instinct not to do it, I chanced a look back.

It was right on me, closer than I had even pictured.

The frothing, grinning teeth were mere inches from my rear wheel. I could see the bits of deer stuck between them. I could even see into that grotesque white eye and the faint, milky pupil staring at me behind the film.

From out of its mouth, a pale, ghostly tongue slithered in and out.

Despite how close it was—as crazy as this is to say—I could not hear it moving. Its legs, which were pounding into the earth to keep up with me, weren’t making any sound at all. No crunching leaves. No haggard panting. Just a silent shape drawing closer. I honestly thought I’d gone deaf in the panic.

I could smell it though—a pungent odor of blood and mange.

All I could do was push harder, pumping my legs like engines that revved higher and higher.

Air battered against my face, none of it making it to my lungs. The trees synced up in my peripheral vision, like slides on a projector screen.

I pulled the phlegm down my throat.

I veered to the right, ducking through a ribcage of skinny branches and then onto a connecting trail. One branch got my cheek, trickling out some blood.

I risked another look. My swerve had gained some space between us. Fuck you, Lassie, my thoughts cheered, as I pushed ahead.

Then the world upturned.

My body was flung forward like a ragdoll as I crashed headfirst into the earth—no chance to adjust or recover.

I fell hard.

The wind was knocked out of me. Colors and textures became red and gritty. My palms were scraped raw, both knees bleeding.

I gathered my bearings, trying to put together what had just happened.

My bike was lying next to me, its old chain snapped completely.

The black shape of the hound was growing larger.

It hadn’t quit.

I kicked off the dirt and broke off toward the closest, fattest tree I could find. Luckily, a large enough oak was nearby.

I planted one dirt-streaked sneaker against it and pushed upward with the other. My hands stretched and managed to grab hold of one of the overhead branches.

I pulled myself up and swung my leg over. At last, a sound reached me—the clack of teeth that barely missed their mark.

The hound fell on its side in silence and quickly scrambled back to its feet.

“Go away!” I screamed at it, “GO AWAY!”

The hound’s face scrunched into a snarl, teeth bared, yet no sound came from it. Foam dribbled over its lips, the gums as white and bloodless as the tongue they shared a space with. Why? Why was it so driven to chase after me? Why was it so freakishly silent?

Because it wants to hunt, and you’re the next catch, my thoughts answered.

I wiped some blood off my cheek, gasping as realization finally caught up with me. I shuffled on the branch, patting down my pockets and turning them inside out. My flip phone was gone.

My eyes scanned around for it, eventually finding its clamshell body lying next to the broken chain, left there from my tumble.

Frustration flared. I smacked the trunk with the side of my fist, crunching one of the lichens growing there into flakey debris.

Nobody knew where I was, save for Joel, who must have known I’d take the shortcut home. Maybe my folks would call his parents to say I hadn’t made it back yet. Maybe they’d call the police to come looking for me in the woods. Maybe they wouldn’t find me. I shook out the thoughts. Too many fucking maybes.

I sighed, wincing at the sting in my palms. At a side glance, I caught something on the tree, carved deeply into its grey bark. No names or initials, just the vague shape of a cat’s head.

The sun went down as more of the forest lost its color. The black hound paced and panted around the tree, its glare never leaving me.

I stared longingly at the rocks surrounding us, wishing I’d been able to grab a few before climbing so that I could peg them at its face, especially at that single cyclops eye.

A deformity, I thought, thinking of all the different sorts of birth defects, like two-headed snakes or an eight-legged goat.

Still, that didn’t explain how the hound was so unnaturally muted. Quiet as a ghost.

✷

Night had now set in. The dark shape appeared to finally lose interest and vanished into the brush.

I’d like to say I waited an hour longer in that tree, but it was probably closer to twenty to thirty minutes that I scanned the area restlessly, slowly building up the bravery to leave my roost.

Somewhere beyond the thickets, a distant owl shrieked.

I was ready. I made my way carefully down and planted both feet on the ground. It provided some relief, like I was one step closer to putting this all behind me.

I made the few paces to my phone and scooped it off the dirt.

The screen beamed with dull life—ten missed calls from home. No doubt, they were waiting to discipline me when I got back, but that was the least of my problems.

I arched my finger to return the call. Something fired out of the darkness—a flurry of silent, thrashing legs and a pallid, sickly orb pulling closer.

I threw myself toward the tree, practically launching myself with each step as I beat desperately toward it.

My hands once again gripped the branch and I hoisted myself up.

This time, I was too slow.

Fangs found my leg and buried themselves deeply inside. Pain welled, shooting up in an erupting flair through me. Branches and leaves meshed in my vision. I let out an agonized cry. The bark splintered into my fingers, but I didn’t dare let go. Somewhere in my mind, I pictured a beartrap clamping its iron teeth into Bambi.

The hound, now balancing on its hind legs, shook its sizable neck muscles, trying to twist me back toward the ground.

Its teeth dug further through the nerves, sending a flurry of pins and needles surging up my leg and scattering around my hip.

With everything I could, I mustered my free leg up and kicked at its muzzle with my heel.

Through some cosmic mercy, its jaws released.

I swung my body the rest of the way up and planted myself back where the height favored me.

Dark blood dripped down my leg and rolled over my sneaker. The pain heaved in waves and hot pulses. I buried my face against the gnarled bark and cried, not wanting to look at the wound, but I forced myself to peek at it. The teeth-shaped grooves left me lightheaded. Don’t faint, I snapped at myself. Don’t you dare faint.

I looked down. My phone once again lay on the ground. I couldn’t help but cry some more.

The hound sat there and stared up at me, its bulbous, cyclopean eye marking me in a world without end. Fresh blood—my blood, this time—reddened the foam around its snout.

It had waited the whole time, queuing itself up for me to let my guard down so it could take me out.

I wasn’t just trapped up there; I was a bird with a broken wing. Thank Christ, the hound couldn’t climb.

I bit back the tears, trying for a moment to picture myself acting tough in front of the guys. It helped somewhat.

I resorted to calling out for help, hoping that, just by chance, someone might hear me and come looking.

The hound once again vanished into the tree line, but I knew there wasn’t a chance in hell I was going down from the tree again. I could still feel the beast there, watching me from the bracken, waiting with tireless patience.

For the rest of the night, I smacked away the gnats and mosquitos trying to eat me alive. Can’t say I blame them; I was probably a smorgasbord for their tiny, alien mouths. I was cold, scared, and hurting.

Every so often, another spasm of pain would shoot through my leg and fill my head with chilling thoughts. Nerve damage. Infection. Amputation. What if I could never run after this? What if there was nothing after this?

It was impossible not to think about. Every time the panic flared back up again, I would scream and shout for help until my throat went dry. Desperately breathless.

An eternity passed. The sky shifted into an orange-blue tone. Sunrise was on the way.

When enough of it brightened the forest, I fell back on shouting for help. Everything hurt, and a tempting need to vomit roiled in the pit of my gut.

I clung to the tree and shouted whenever enough air allowed it.

✷

“Hey, everything okay?” A man’s voice eventually called.

I looked down. There was a young couple parked on waspy-yellow bikes, both of them wearing bright Lycra jerseys. They’d happened to be riding the trails that early morning and heard my cries.

“Kid,” the tallish man called again. “Are you okay?”

“There’s a dog!” I shouted back. “Watch out!”

Both their necks swiveled but then returned to me.

The man approached my tree. The braided-haired girl remained on the trail, watching cautiously.

I expected the one-eyed dog to burst through the growth at any moment and fall upon the man, while the woman recoiled in horror.

But nothing happened. The hound had apparently gone away.

They took me to the hospital where I got several stitches for the bite, a tetanus shot, and the first of a scheduled series of five anti-rabies shots.

I was half expecting to still be reamed by my folks for putting myself in that position. But they were just happy I’d made it back home. Going from offender to survivor will do that for you.

✷

Even as my friends ribbed me, calling me scared or too chickenshit, I refused to ever step back into that godforsaken place.

For the next three or so years, I dreamed about the hound. But in my dreams, I would never make it to that tree. My bike would fall apart. My legs would seize up completely. And even if I did reach the tree in some cases, the feeble branch I grabbed would snap and send me falling back into the jaws that wanted my life.

In the summer of 2000, I went to prom with Rylee Dean. She was a timid girl, surprisingly skittish for a cheerleader. We were absolute opposites and, to be honest with you, I never thought she’d say yes when I asked her to go with me.

Halfway through the night, she couldn’t find her inhaler. It had been left in my car. I set out to get it for her.

I made my way across the parking lot, pulled the keys out of my pocket, and fiddled with the lock.

From under the car, something snapped at my leg.

I fell back onto the pavement, my hands and ass breaking my fall.

A black shape sprang forward from beneath the car and seized the cuff of my dress pants.

It was back. The hound.

That same oily fur, the wriggling, slinking, white tongue, and that one hellish eye holding no signs of life.

I screamed and kicked frantically, blubbering for help like a lost child. My pants fabric ripped in its teeth.

It launched again, this time finding flesh instead of polyester.

The pain ripped through me, sending me five years back—to that night in the woods, screaming for help.

Some people heard the commotion and ran over.

The hound unclenched its teeth and ran off into the distance.

I stared at the new ring of bite marks etched into my leg. Marked once again. An ambulance was called, and poor Rylee Dean’s prom was cut short by an ambulance ride for her prom date.

I wish I could say that it was some sick stroke of bad luck, that I’d just so happened to run into the same dog that had attacked me years earlier. But it was more than that.

It took me two years after the second ambush to realize it.

✷

I moved out of Tally and went out of state to pursue college. I couldn’t afford to live on campus, so I ended up leasing a small place in a close enough town. The house had already been pre-installed with motion lights outside.

One night, while I was in the kitchen, I saw that the backyard sensors had gone up. Figuring it was a cat or some other small critter, I went to check it out.

I opened the back door and looked out. What I saw made the glass of water slip from my hand and clatter onto the floor. All I could do was stand there, the inner parts of my throat seizing up and choking me, the sharp, mangey smell finding my nostrils again.

Trauma always finds a way home.

The hound sat in my backyard. Back once again to take another piece out of me. Its mouth open in a teeth-baring growl, never to make a sound.

I’m not finished, its large, lifeless eye said. We aren’t done yet.

The scars on my leg burned, marked forever and always.

I closed the door, locked it, and walked upstairs to my bedroom. There was not much else I could do.

For half a moment, I actually thought about calling animal control and telling them a rabid dog was loose in my yard. But the beast would be gone by then. It was always gone by then.

✷

The hound has come several times since then. Bounding at me from a dark alley. Leaping out from behind a tree. A shadow forever hunting me. And just how long until it bursts out of my closet, gunning for my neck?

I’ve since bought a pistol, and the loaded chamber never leaves my side. Who knows if it will even do anything to that thing, but I’ll die before it ever manages to catch me off guard again.

Sometimes I even think about going back to Tally, where I know more kids are surely playing around those woods. Exploring places. Running into things they shouldn’t.

“Go home! Stay out of the woods!” I’d shout at them. “Stay the fuck out of those woods.”

✷

Michael Paige's work has been included in several literary magazines such as The Furious Gazelle, The Scarlet Leaf Review, MetaStellar, Midnight Magazine, The Horror Zine, as well as printed & digital anthologies for Savage Realms Press, Crimson Pinnacle Press, Ill-Advised Records, Gravelight Press, October Nights Press, Media Macabre, Little Red Bird Publishing, Chilling Tales for Dark Nights, Culture Cult, Skywatcher Press, and also a charity anthology for Great Lakes Horror Anthology (GLAHW). Check out his blog, Twitter, and Facebook for more.

"Forever and Always" was originally published on the author's website, and is accompanied by a narration.