✷

The road to the highland path ended long ago, gravel turning to dust turning to mud. The mountain is flat like a stepped-on fern frond. Eden’s feet ache, and her amber-cast beetle necklace thuds against the hollow of her chest with every step. Lauria gave it to her before she moved. Eden grasps the frayed ends together to keep it from falling apart.

In the valley beneath the trail, glimpses of rubble and stones and the open maws of old mines flash through the landscape. She tries to ignore them and fails, the emptiness of the caves matching the weight in her chest.

Not much further, now. It’s a relief when the trail curves away from the mountain ridge.

A vulture circles. It cries out and Eden’s head jerks up, her attention caught by the sway of its feathers in the sky. She categorizes the bones of its wings in her head and gets to metacarpus before she trips on a withered tree root — the bird is injured, she can tell, and if she were at work, she would take it in for surgery. When she stands again, flecks of snow fall off the grasses and flutter onto her thighs, melting into the fabric of her jeans.

In the distance, a small house stands against stained parchment sky. Peeling wood shingles cover the exterior, light blue paint flaking off into nothingness. She picks up her pace, winding through a spider-web of grasses despite the wind on the ridge howling into her eyes. Nightfall comes faster on the mountains, sunlight entangling itself in the moors, and it would be best to be at the house before dark.

Eden steps on one of the trail-stones. It cracks under her weight, the sound a thunderbolt in the silent skies.

The vulture is long-gone.

✷

She was in the bar, perched on a plastic-coated stool at an empty counter-top. It was sticky with spilled beer despite the deserted streets and the winter sun razing on broken asphalt outside. Shards of light wormed their way through the plywood covering the broken window and flickered on the scratched linoleum. Rebuilding in town was slow, even then.

At the opposite end of the bar, another person sat, alone. Their face wasn’t familiar, which was odd, since she should have been able to recognize them from the grocery store or her high-school or the mountain rescue crew that came to the bar every Thursday night.

“Where ya from?” she asked, tipping back her drink to hide the creak of her voice. It had been some time since she had spoken. The bartender wiped down the counter and said nothing.

“Three towns over,” they said. “Here for the ski slopes.”

She looked outside. There was no snow on the ground; it was covered in dead lichens. The sun glared on the unmoving chairlift swaying in the wind. Across the street where the house she grew up in used to be, a goshawk perched on a rusted truck.

She took another drink. Her head ached.

“Really?”

“Well, that and work.”

Their answer wasn’t much more convincing, and the scrunch of their face reminded her of the horned owl she tried to give a shot a week ago — skittish and uncomfortable. There weren’t any jobs in town. There hadn’t been for two years, not since the old mines caved in, not since the avalanche.

The stranger was still silent, their eyes the same hazel-green as her own, though glassier, and the wound of a conversation stretched open into a knife-cut. She tried to suture it.

“What d’ya do?”

Their face twisted. The question acted more like a leech than a bandage, but they answered, nonetheless.

“Don’t remember.”

Silence hung in the hair, oppressive like smoke hovering over the valley. The stranger sighed, gesturing up the mountain to where overgrown trails erupted from the treeline.

“There’s a house over there,” they said. “Up the mountain. There’s a thing—”

Their eyes lose focus as they continue. “—Makes you forget. Or somethin’.”

She shared a glance with the bartender. This was the usual, crazies who work their way through the mountains in the off-season, looking for the newest drugs or the newest drink, whichever is cheapest. When she looked back at the stranger, though, the coal and scabs on the tips of their fingers dragged her thoughts to the blank look on Lauria’s face being hauled out of the rubble seven days after the cave-in. Her own hands shook as she took another sip from her glass, ignoring the pang of familiarity the feeling brought.

The glint in the stranger’s eyes is the same as Lauria’s back then, too, though it had been long enough since she has seen her that she’s not certain she remembers what Lauria looks like. Eden peered out the window, watching an eagle soar through the clouds, and said nothing when the stranger pushed cash across the counter and walked out.

✷

There are still feathers on her shirt from the morning’s capture and release, a red-tailed hawk caught in an old zipline system, and they scratch at her arms as she walks. The house is still a thousand paces away. Eden swears to herself and trudges up the path, the soreness of her feet transfiguring into a preacher’s fury. It’s getting dark already, and the shadows carry memories she would rather not see.

✷

Seven months after Eden met the stranger in the bar, she walked into the library. She threw away her half-full coffee cup — it tasted like sandpaper anyways— and swung the door open as the conversation of the teenagers outside faded.

When she reached the front desk, she saw Don. She didn’t really mean to ask him. It’s just that Don was standing there, and Don had manned the library desk since she was a child, and Don would almost certainly know about a house up on the mountain and something that gets rid of memories living inside it, and Don looked older than she remembered, skin hanging off of his bones, and Don was suddenly closer to being dead than she had ever let herself think.

“The house up on the mountain?” he muttered. His eyes widened. “Why?”

“Heard it somewhere,” she said, avoiding the squirm in her chest.

He squinted as he looked her over. She couldn’t tell if there was something too telling in her bedraggled hair or the bird scratches on her arm or if it was just the sun in his eyes. Or maybe there were coal smudges on her face, even though it had been two years.

He shifted the worn-out baseball cap on his head. The veteran insignia embroidered into the brim was fading.

“If you wan’ta forget something,” Don began, and she heard him hesitate. “There’s a woman on the edge of town. You probably know the house, the one that looks like it’s been abandoned with the red paint ‘round the door. It’s not the house, but…” he said, and he leaned in like he was sharing a joke. She didn’t quite understand why.

“But the lady there knows more ‘bout it than I do,” he finished, scanning a gem encyclopedia and stacking it on the pile in front of him.

She nodded and turned to leave, forgetting about the books she had on hold, and pretended like she wasn’t about to rush down the cracked asphalt and drive straight to the outskirts of town in her beaten-up coupe.

Don spoke again. “I went.”

She turned back around. The look in his eyes was imperceptible, something weighing on him that couldn’t possibly be the war, and she opened her mouth to ask him a thousand questions. Then she closed it and walked out. She saw him nod in the reflection of the glass as she closed the door behind her, and she flinched when the click of the handle echoed like a coffin lid.

✷

She is almost to the house, the trail straightening as she crosses the ridge. The air tastes of dried bonfire and bleach, and the front garden is under siege from thorn-covered vines. She sniffs. The air smells like rain — wet ground and another cave-in written in the wind — and the scattered gravel of what was once a patio crunches under her feet and eats into her socks as she climbs the last steps.

All her life she’s lived in town, and she’s never climbed the mountains. Her therapist had said to make changes. Lauria would be proud.

The porch does little to protect her from the wind. There’s no knocker on the front door and she can’t see through the frost-coated windows, so she reaches straight for the handle. It swings open at the faintest touch.

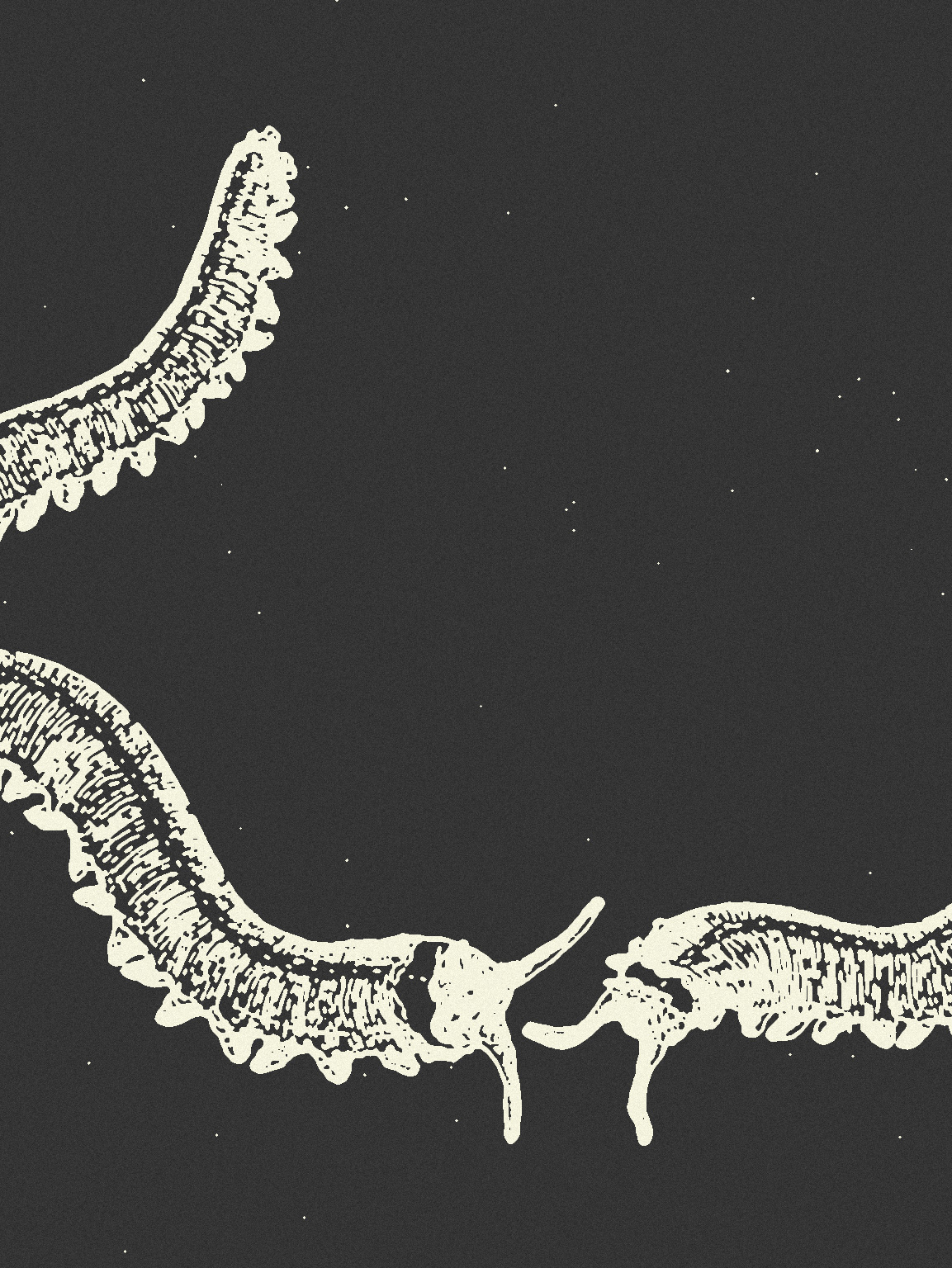

The hallway is limestone bare. Bleached white bones hang on the walls in place of picture frames. A gust rushes over the mountains, pushing through the doorframe and weaving an echoing wail in the innards of a deer skull. She holds her necklace up to the fading daylight. The beetle inside looks like a smudge, dark and blurry.

For a moment Eden’s foot hovers on the wood steps, about to run back down the mountain and to her car and out of town to Lauria’s new apartment, but she stops herself and takes a breath. There’s no coal caught under her fingernails. It feels like there is.

She steps over the threshold.

✷

The woman on the edge of town was much younger than Eden thought she would be. She had envisioned an ancient woman clinging to life like a barnacle. She wasn’t. Eden had passed under the garish sign reading Heather Moonraven’s Tarot Readings barely thirty minutes ago, and she had been offered three tinctures and one palm reading in that time.

“What are you even here for, then?” Heather asked, after she refused a fourth tincture. She was tapping away on her phone, acrylic nails clicking against the glass screen.

“Don told me you know about the house on the mountain?”

Heather set her phone down and looked up. Her mascara was thick enough to be the engraving on a gravestone. “Who?”

“The librarian.”

“Why?”

“Just curiosity,” she lied, and Heather laughed. A clump of hair, white-girl dreadlocks sticky with wax and dollar-store thread, fell over her shoulder. Her earrings were made of kestrel feathers; Eden tried not to wince when she saw them.

“Of course,” Heather said, sarcasm dripping in her voice.

Eden coughed and sipped her coffee. It had gin in it this time, only a drop or two. “I might have something to forget.”

Heather’s voice sharpened. “There is a woman, a thing, up on that hill,” she said. “They call it the Story Eater.”

She paused. “If there is something that needs to be forgotten.”

Eden left Heather’s house an hour later, pockets five dollars lighter for what Heather had called a consultation fee. As she walked back to her car, she cast a glance to the top of the mountain, where a single power line arcing through the sky marked the trailhead. She saw nothing, no house that Heather had said would be there — only open gray sky. The emptiness might have been her imagination, just like her therapist had said the memories haunting her are.

A bird flew into the transformer and collapsed to the ground, dead.

✷

She hears a quiet voice. From where she stands in the hallway, it takes a minute to dissect it from the wailing of air against the bones.

“What brings you?” it rasps.

Eden stumbles as she turns the corner into the main room too quickly.

The thing that lives in the house on the mountain is tall, hunched over a cane, dark tattoos written into its wrinkles like the scrawl of ink on vellum, contrasting with bright white hair. She can’t remember the eyes. Other than the rocking chair, the living room is empty.

She takes a step forward and the Story Eater raises a hand to stop her.

“You may still leave,” it intones in a sound that seems like kindness.

She nods and steps forward again. And then the stories are there, faster than she can tell them. The thunder of something breaking in the entrance above her, rocks clattering down onto her and Lauria like their heads were geodes to be split. The week spent lost in the channels and passageways and crevices of the old mines, utter darkness forcing her eyes to reach for something that wasn’t there. The rotten fish she and Lauria smelled but never saw, the pang of hunger from three days wandering in darkness, fighting her urge to vomit. The crevasse Lauria had slipped into, unseeing, her nails scrabbling against rock and stone while Eden had tried to pull her out by the arms and slowly lost her grip. The hallucinations conjured by her mind as she stared into nothingness, flightless birds and shining minerals glittering on the walls of the caves, a mirage.

She pauses for a moment, her throat dry, and sees the Story Eater — its eyes closed and mouth open, teeth too sharp.

The words keep coming, the things she didn’t tell Lauria from the days they were separated.

The oil-slick stains she had felt under her fingertips as she walked alongside an underground stream, rushing water vibrating with the shake in her breath. The sandpaper scratch of her throat from dust embedded in the water. The stones she tripped over — the memory is blank, now. What was it about the stones? The moss, finally, moss, that she had found after four days of wandering, near the collapsed entrance, which had been stuck under her ring-finger’s nail for months after she and Lauria had been taken from the mines, months after she had walked back into the sunlight and seen an avalanche of rocks burying the only town she had ever known. The shadow she had seen in the caves, always following a foot behind her, that she was sure had been a hallucination until she turned around in the sunlight and saw something unnaturally dark lingering in the depths — the memory is gone. She searches for the next words and finds blankness.

She opens her eyes and sees what looks like a tall, old figure standing in front of her. She knows it is called the Story Eater, and nothing else.

The figure smiles. “Is there anything else you would like to forget?”

Else? She thinks.

Its cheeks are plump, and it looks hungry.

She staggers out of the house, falling down the mountain path. When she turns around, there is no house and no memory at all. There are faint lines of coal-ash staining her hands and rocks stuck under her fingernails. She doesn’t know why.

• • •

Piper Farmer (she/her) is a writer and student living alternately between Pennsylvania and the coastline of North Carolina. She's interested in all things medieval, mythological, environmental, and of course any good cup of tea. You can find her at piperf.substack.com.