✷

I was born under a creamy harvest moon. My mother spent a whole night screaming and hunkering down on the floor, my tiny body blue and floppy and still tethered to her like a fish on a line. It was a difficult birth. My grandmother had predicted as much, because three nights in a row she’d seen a greenish shadow shifting like a veil in the cold sky. Three was a bad number. It was two playing happily together and one left out. It was a pair and a spare. Two golden daughters and one stillborn son. It never meant anything good.

The old learnings are never wrong. I know that now. They are vines creeping through the foundations of civilisations, wisdoms too many of us have forgotten; they coil around your ankles and trip you when ignored. I made fun of them when I was older, but the moment there were three of us in the hut, the evil eye was upon us. As I grew big and strong, dandled on Grandmother’s knee, she was slipping away from us, a little less solid and present every day. My mother had put her to bed and shut up the sleeping room before the year was out. But that was fair, because I was new to the world and Grandmother was old. An eye for an eye, a life for a life.

“Balance is restored,” my mother said when the spring came and we were two again. I would have liked a sibling to tussle with, but I had to make do with the other village children, because obviously you couldn’t do that with your death. We roiled and scuffled like fox cubs in the snow until our cheeks were ruddy and our muscles strong. If you howled into the valley, your voice bounced back to you ten times over, like a pack of invisible wolves. I’d never seen a real wolf but I sometimes felt like I had one inside me: restless, prowling, voracious for food and fire. My mother got tired of me and my death tossing and turning beside her and hers all night long on the other side of the narrow kitchen bench, so finally she unlocked the sleeping room and flung the window wide, slapping the dust from the bedclothes. All the stale air rushed out and a glacial gust filled the house, so sharp you could whet a knife on it.

I did not cry when it was her turn to die. It had been a hazy thin summer and now we were heading into another lean winter. The bones of my back dug into the floor even when I slept in my father’s hunting furs. Everything I ate went straight towards making my legs longer and my hips wider, and to my monthly bleeding. But it wasn’t enough. The growth drew from other sources, sapping the baby fat from my stomach and filing down my cheeks. Maybe it sapped my mother, too, the same way she had nourished me in the womb. She was growing transparent like Grandmother, freckles fading, skin like buttercream. I had my father’s dark colouring and his upright bearing; I did not stand apologetically, cringing into myself, like my mother did. It was a habit she and her death had learned—this way of turning yourself near invisible if you so much as looked at them too hard. I looked like my father, and he had been cruel to my mother. Maybe that was why she and her death hated me. Hatred did not come easily to her, though. She held out scraps of love for me at arm’s length, only to snatch them away an inch from my jaws. It would have been kinder to let me starve completely. But my death and I fended for ourselves and found what we needed elsewhere. Our reflection had hungry eyes.

✷

The day of her death, I had gone to the silver birch forest. It was a two-hour trek from the hut, but I needed the space, the fresh air. My mother didn’t approve because sometimes children forgot their way back—but it was the best place in the whole of the Territory to hide, sing, dream. It was the one place you didn’t go to scavenge or to hunt. It was sacred ground.

Ingen was sitting in the hollow of my favourite rock, the one shaped like a giant’s soup spoon. He nodded in my direction.

“Hail,” he said. He was whittling something tiny—a pipe, an ornament. His death sat cross-legged beside him, eyeing mine. I watched his skilled hands grip the bleached bone.

“Who’s it for?” I asked. Whatever it was, I wanted it.

“My mother,” he said, just to mock me. Then he put the knife down and read my face. He never just looked—he had the kind of eyes that go deep, not the soft ones that just skim the surface. He knew I was ravenous for anything he could give me. Suddenly his hard hands were round my ankles and my death and I tumbled to the ground, shedding our furs as we fell.

We had been doing this whenever we could since last summer. The first time, I was picking bilberries and he tumbled me in the rushes. Sometimes he still made me bleed, but he didn’t like it when that happened. I liked it. It was a wound you were allowed to enjoy—being impaled with a victor’s snarl hot in your teeth. It was the only time Ingen was ever capable of cruelty.

Finally we rolled over, our breath dissolving into the branches that crackled the sky like a glaze. I loved how my death looked after Ingen and I had mated. She was tranquil but elated, a goddess of her own domain.

✷

I didn’t get home until the cold sun had scudded halfway across the sky. I was late preparing the repast, but my mother said nothing. Her face was haggard, eyes bloodshot. By this point, I could barely tell which shadowy figure was her and which was her death. The four of us finally sat down to a thin soup at the scrubbed kitchen table. My mother didn’t touch her steaming bowl. Her colourless eyes settled on the little bone bear I hadn’t let go of since I’d got home. I hated the void into which her words and my father had disappeared. They filled the hut like a heavy cloud.

“I’m done,” I said, pushing my empty bowl away. “Are you going to eat that?”

My mother looked at me as though the question was beyond her comprehension. I grabbed her portion and devoured it, the herbs gritty in my throat.

Then her death spoke. It was the first time I had ever heard her voice, cold and firm and authoritative.

“Let’s go.”

My mother rose unsteadily, clinging to the table for support.

“Come,” Death said, not without a certain gentleness. “It’s time.”

A low moan escaped my mother. Taking her arm, Death led her across the hut. Wasted and frail as she was, she looked like a little child with their guardian. She moved like a dreamer, half drifting, half stumbling into the sleeping room.

When the door closed behind them, I did not follow. You did not come between a person and their death. Besides, there was no reason for me to be there.

When I could no longer hear Death’s impassive monotone, I took three steps towards the door and placed my palm upon it. All around me, the hut rang with silence, trembling like a struck gong. Little by little, I inched my weight forward until the door creaked open under my hand.

The room was empty. My mother and her death were gone.

Immediately I got to work, casting the window wide open, stripping the bed bare. The blankets and furs were damp with a cold sweat. I snapped each twig of the wicker mattress and tossed it on the fire, crushed herbs beneath my feet. All this had to be done before the sun rose on a new day, else my mother and her death would never reach the next world; they’d simply evaporate with the morning dew. Though it was probably just another old story, I worked swiftly all the same, sealing the door forever to prevent the spirit from returning. I had no boards or nails, but I had twine. Tying and weaving, I wound it around the door like the web of a crazed spider. Finally I stood back to regard my handiwork. The ritual was complete. The last bit of common human decency I could give my mother.

Normally there would be a vigil outside the room in the morning, but the only person who’d really known my mother was Ingen, and if the two of us were alone together, mourning was the last thing we’d feel like doing. I lit a candle and forced myself to think of her, to dredge up happy memories we’d shared, but it was strange to think that she’d sat at the table this very morning, even scolded me for wearing through my boots so quickly, and a matter of hours later I was all alone in the world. Perhaps Grandmother had come back to get Mother. Perhaps it was because she’d unlocked the sleeping room…

Shaking my head, I blew out the candle. The moon was a vast milky orb by now, huger than I had ever seen it. I curled up in front of the fire and fell asleep with Ingen’s bear clutched tight in my fist.

✷

An unknowable stretch of time later, I started awake as though I had been struck. Everything was white. For one bleary second, I thought I had gone blind, but it was just the sky, torn along its seams and shedding blizzard tears. On autopilot, I listened for the sounds of my mother waking, but then I caught sight of the sealed door, and I remembered. It was strange. Even the flagstones felt wrong under my feet. The air she should have occupied vibrated with her absence.

I needed company, I needed human warmth. I made myself a meagre pack, laced up my boots and fought my way downhill.

✷

The cold seared my skin and lungs, but it felt good, cleansing. With every step I felt a little better. Airy fantasies of starting afresh rose up before my mind’s eye. Perhaps Ingen and I would go south until the naked trees sprouted green fronds and sumptuous fruits and the frozen expanses melted into sapphire seas.

Presently I approached the halo of birches that demarcated Ingen’s family’s land from the rest of the wilderness. Ingen’s father had dealt in rare furs in the before times, and they lived off their riches. I recognised Ingen’s little sister crouching down in the snow.

“Hail, Tarra,” I shouted.

Tarra gave a start, her expression stricken. Her eyes were swollen and red, pieces of golden hair sticking out of her braided crown like tufts of straw. She wasn’t building snow animals—she was frantically scrabbling around in it as though trying to bury something, wailing all the while. Her little mittens were soaked through, the wool red.

I grabbed her wrists to make her look at me; she squirmed and snatched herself away. “What happened, Tarra?”

But Tarra just kept burrowing frantically.

“Say something!” All at once I was shaking her like a rag doll, my fear amplifying hers; she began to scream, clawing at my face. “What happened?”

“TARRA!”

At the sound of Mileyna’s voice, I let go. Tarra fell to her knees. Ingen’s mother dragged her up and pulled her sobbing to her breast, eyes blazing.

“Get inside,” she barked at me. “It’s not safe out here.”

“Mileyna, where’s Ingen?”

Mileyna shook her head. “Gone,” she said without emotion. “Spee poachers. Got him in the woods.”

Before she’d even finished speaking I’d run headlong into the forest, screaming Ingen’s name. My knife was small, but it was strong and sharp, freshly whetted. Maybe that, coupled with my rage, would be enough.

But then Ingen’s hunting dog Emmy came hurtling towards me with blood on her muzzle.

“Oh, sweetie,” I cooed, crouching down and feeding her a scrap of meat from my pack. “Where is he? Take me to him.”

Emmy shook like a leaf, cowering against my legs.

“Come on,” I said. “Please, Emmy.” I held the rest of the meat out like an offering, just beyond her reach.

With a doleful little howl, Emmy turned and wound through the trees. I followed. Our breath billowed out in front of us in great clouds. As we crept closer to the heart of the forest, the thatch of bare branches above us grew thicker, casting strange shadows on the tight-packed soil. I began to see signs of human life—partial footprints in the marshier spots, made by heavy boots; a burned-out bonfire crowned by a cluster of animal bones picked clean; and worst of all, the smell. The Spee left behind a kind of metallic stink—very different from the scent of pine needles and leather I associated with my own folk. It was like they were marking our territory to make it theirs. My mouth turned sour. Curse you who raped our women and murdered our children and scattered the rest of us to the four winds. Curse you who took my father away.

Just then, a rustle in the undergrowth made me jump. I lunged for my knife.

But it wasn’t a filthy Spee. It was Ingen himself, his death leading him by the hand.

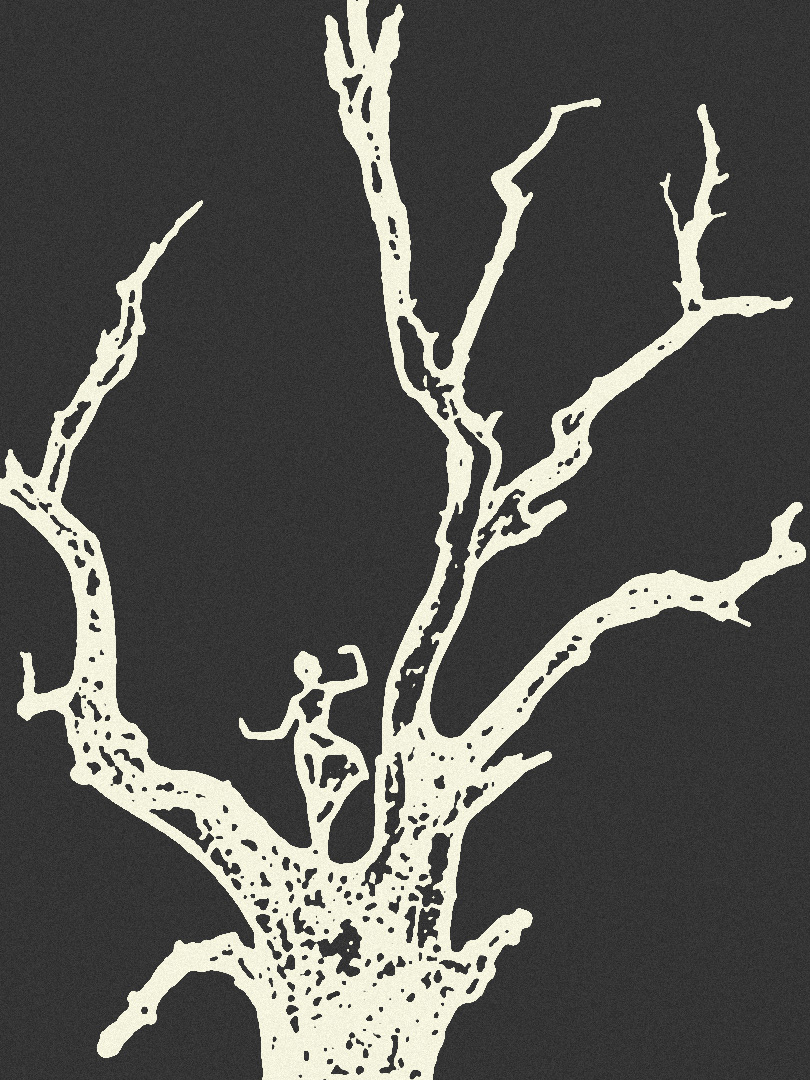

I cringed into the sturdy ash behind me, wishing I could melt into its bark and hide myself forever. Emmy was frozen at my feet. We weren’t supposed to see this. But oh, Ingen was beautiful. He was striding tall and proud and upright, his skin translucent. The river ran through him; the trees were his bones. The mouth that had feasted on me in secret afternoons now gave me a vague smile, as though I might have been someone it had once tasted. He and his death disappeared into the mist.

As though in a trance, I sought the scene of his passing.

Emmy let out a fresh volley of howls when the beartrap materialised before us, a gaping maw of iron, sullied with Ingen’s blood.

I tore off my gloves and scooped up the bloody snow, drinking from the bowl of my cupped hands. It tasted like the tears I couldn’t remember how to cry.

✷

It was a slow and solitary walk back out of the woods. I wrapped my arms tight around myself as if to hold my shattered self together. The nightmare kept replaying itself over and over in my head, embellished more gruesomely every time—Ingen crying out in shock, felled like a tree, flesh tearing, bones snapping.

All the while, my death stood impassive.

“Can we follow him?” I asked her.

“No. It isn’t our time.”

“Then when is our time?”

“I don’t know.”

“Tell me.”

“I am telling you. I won’t know until the time comes.”

I wanted to make her hurt like I was hurting. Could you kill your own death? I had no idea.

I kissed the little bone bear on the nose and made to tuck it into my tunic, next to my heart, but the biting wind was too cruel to remove any of my layers. I put it in my pocket instead.

✷

Distracted as I’d been, I hadn’t registered the day slipping away from me. The light was fading fast now. Panic seized me. My mad flight had brought me further than I had ever ventured before. Even if I started running back in the direction I’d come, the darkness would fall too quickly for me to find my way out. All I could do now was stay in place and hope to stay alive until morning.

Whilst a little light remained, I cleared a patch in the undergrowth to start a fire. The twigs were damp, and it took several minutes of concentrated effort to get the spark to catch. Then a tongue of flame licked along the length of the wood and flared. My numb fingers stung as they thawed. There was such pleasure in the sensation that it took me longer than it should have to realise I was not alone.

A juvenile bear was snuffling around in the undergrowth, bones sharp beneath his black-brown fur. He was the first wild animal I’d seen in months; hunger had made him incautious. Feeling my eyes upon him, he raised his great shaggy head and regarded me for a long, sad moment. Neither of us moved.

A watchfulness settled deep in my core.

At last, deciding I was neither a threat nor a meal, the bear began to amble clumsily away through the trees.

A great fullness swelled in my ribcage.

He is there for you, I told myself. Ingen has sent you a gift.

Running up behind him on the balls of my feet, I held my breath and plunged my knife deep into the bear’s great thigh.

He bellowed in outrage and shock, turning his withered bulk on me, but I had the advantage of speed. I had to finish what I’d started. I flung myself onto the animal’s broad back.

The roar shook both our bodies, making my ears ring. The bear’s head jerked, teeth gleaming in a rank snarl, but he couldn’t reach me, clinging to his matted fur like a tick. He reared, backing up against a tree to crush me. I fell to the ground just in time, and he loomed over me the way Ingen used to do when we rutted like mad things in secret places. Pity and hunger warred in my heart.

“I’m sorry,” I panted as I drove the blade into his exposed belly.

It tore him upwards as he screamed, voiding a foul torrent of hot guts before collapsing onto me.

It took me a good ten minutes to work myself free from his dead weight. The entrails steamed in the snow. Sweat chilled me all over. I had to get warm, inside and out. In the wilderness, people froze to death on warmer nights than these.

✷

By the time the moon had reached its zenith, I was sitting before the fire, wrapped in bearskin and holding a skewer of meat to the flames. Water collected in my mouth as the savoury smell filled the air and the meat began to spit. It was lean and gamey, chewy in texture. I ate until my belly ached. The first pinpricks of stars began to pierce the violet sky. I thought of my ancestors’ paradise. Did any of them ever make it there?

A sudden sound behind me broke my reverie. Instantly my body tensed, senses on high alert. That was no animal sound—it was too rhythmic, too deliberate. My heart dropped into my stomach. Yes, it was unmistakable: the voices of men coming closer.

I ran low to the ground and flung myself flat in the bushes, hiding under the bear’s pelt.

Heavy footsteps approached and stopped an inch from my head.

Please, no. Please go, I begged silently—but a swift hand flung the fur aside.

“Well!” The poacher grinned through rotten teeth; the stink of his breath wafted down into my face. “What are you doing here, little cub?”

He snatched the fur from me with a suddenness that made me jump, and tossed it into the fire. “That’s one cub I wouldn’t mind stroking,” another man said.

Cruel laughs sounded in the darkness. I cast about, making out a group of six Spees with hard, glittering eyes. They wore the traditional ornaments and amulets of the North: animal teeth, claws on cords around their waists. Not only that—alongside the sharp curved knives at their belts, they clutched crude giant’s weapons: hefty clubs, jagged axes, and other strange shapes I couldn’t make out in the dark.

The men began to explore my campsite, digging through my pack before kicking it aside, picking more meat from the bear carcass. One of them, rather shorter than the others, remained where he was, eyes roving over my body. Had my mouth not been so dry, I would have spat. In response, he smoothed his hands down the length of his torso, gesturing roundly over his chest—and then jerking his fingers in and out of his other hand with such gusto that the quiver of arrows strapped to his back rattled. Raucous laughter ricocheted around the clearing. I trembled with cold and fear and fury. If they chose to lay their hands on me, I would be no match for them. I would end up like my father.

My fingers crept along my hip towards the handle of my knife. Twin animal instincts—to make myself smaller, to make myself bigger—electrified every nerve. An inner war. A single choice.

I stood up.

It was my last mistake.

A hard shock hit me in the back with such force that I stumbled, arms out to break my fall. Sharp little gasps escaped me. I was pierced right through by my enemy’s arrow: the head embedded in my heart, the shaft sticking out of my back like a broken wing.

My killer was younger than I’d thought—smooth-faced and suddenly unsure of himself. All that heady confidence had just been for show. I saw that now. His eyes grew wide. Wrongfooted, he shook his head—in apology? —walking slowly backwards.

My fingers scrabbled helplessly at the arrow protruding from my chest, the hot blood spurting through the layers of furs. I collapsed onto my side, curled up in agony.

The rest of the Spees quarrelled like squabbling birds, and then they scattered. I half-closed my eyes. My mind seemed very far away, somehow. On the ground, it was almost peaceful.

I gradually became aware of a lone figure kneeling beside me in the mist. For one confused moment I thought it was my mother, but it was Death, my death, the death I had known all my life, the death that bore my own face. She was Death as I had never seen her before—finally corporeal, solid to the touch. Her loose dark hair cascaded over my shoulders, her breath warm on my neck. Taking my knife, she sliced the shaft of the arrow from my back in one swift stroke.

A jolt of electric pain seared my core. My vision turned black, and a faint pressure pulsed dully in my ears as though I was drowning in pure air.

Cool hands rolled me onto my back; the snow burned and cooled, was hard as stone and soft as eiderdown... I knew nothing for sure. Pain and pleasure had embraced and become one, just like I’d always known they were.

Death placed her hands either side of my wound. The blood had long ceased to flow, frozen and congealed in the furs. She pulled the arrowhead free and looked at me with tranquil eyes.

The wind blew through me.

“Ready?” she said.

Raising me to my feet, Death divested me of my sullied and broken body, opening the cage of my ribs to let my spirit out. Then she stepped back, watchful, reverent.

The body was mine to bid farewell. I had never truly owned it. It was time to rescind it to Nature.

“Thank you,” I told the shell of myself, embedding the bone bear in the bruised pulp of its heart. At my touch, my corpse dissolved into smoke, coiling up into the moveless sky. All that I had ever been was another fistful of ashes on the fire.

I turned away from my life and took Death by the hand. Together we walked out, away, far and forever beyond the night.

✷

Lesley Warren lives for language. A translator born to Welsh and Filipino parents and now a resident of Germany, she writes extensively on themes of "otherness" and identity. Her poetry and prose have been featured in a number of print and digital publications as well as a podcast.