✷

The horizon greedily snatched the setting sun in a flash of white light.

Day after day, a young boy viewed this natural act of mockery atop brown roof tiling. Week after week, his expression drooped into a look of despondence. It was a never-ending cycle, or so it seemed. He had even imagined an accompanying voice that quietly whispered, “lights off,” as if to reinforce the bedtime curfew.

Still, he did not listen. No one had explained why he needed to remain on this lonely isle, and so he would keep checking for impending signs of rescue.

His three-floor home was a crooked, architectural mess of misshapen windows and hollow doors, its pale olive bricks pockmarked by greenery in the form of vines woven throughout the structure. They filled the bone-like cracks in mortar, staved off the natural erosion of the tide’s pull. In that sense, unbidden life force was continually infused into the clay sediment that encircled the property.

The boy also shared one mind with the place he had resided for the better part of six months, and knew it desired the same thing as him: to sail rebelliously against the sterile winds.

But there were complications. A chill kissed and cradled him with malice from behind; the tendrils had a deliberate way of tapping him on the shoulder when he had time to dream.

He was not quite so alone.

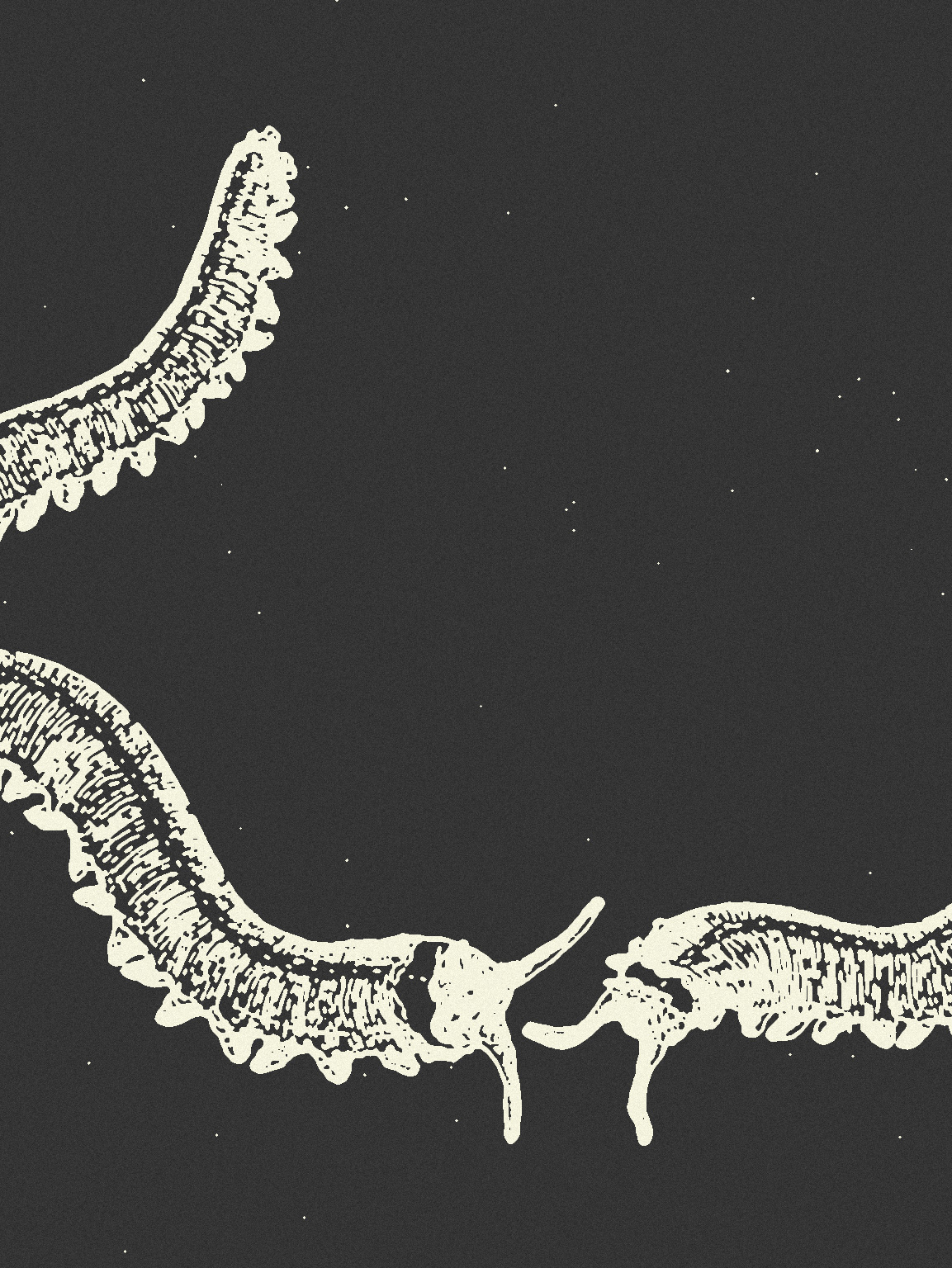

Fifty leagues to his rear, there grew a dark spot, rising and taking root like mangroves in a shallow riverbed. Jagged spires of branch-like extensions radiated outwards, meeting the tallest level of the boy’s tenement. It rotted everything it touched: water turned into filth, seabirds turned into embalmed carcasses, and saplings turned into brown shrubs. He had seen it firsthand when a spindle of vines dropped off and floated into the black tendril’s clutches.

It lay in wait. His temporary home could not relocate. The boy was stuck with the threat.

He sought seclusion in the attic sometimes. In there, the black spot was not visible, but the images lingered uncomfortably. They fluttered in-and-out, in-and-out, in-and-out; like ghostly specters dancing on icicles, they haunted his waking nightmare. And that was appropriate, as the boy thought only of death, a subject matter his parents cried about upon hearing. He did not understand why.

What else was there for him in this painful monotony?

Every morning and evening, a collection of men and women rowed a wooden boat and hitched a noose to his isle—it anchored their craft. They were the same ones over and over, so the boy recognised their faces, their masks and their concerned looks. They did not speak to him, but rather at him.

“Your parents cannot visit you for a couple more weeks,” they slurred in unison. He did not hear much of what they said after that.

In the wake of their craft, they injected a wave of frothing chemical spray that crashed through the lower level of the house, its load-bearing bones whimpering. The boy braced with both hands on a windowsill inside his bedroom; where pressure was applied, his extremities popped with a smudge of blue bruising. The same could be said of the terraced rooftop. It used to have a garden at its peak, containing floral arrangements of daffodils, carnations, lilies and the occasional sunflower. The boat had shaken these free with repetitive disruption, and the boy wilted a little as they did without soil to nourish them.

There was only one thing about the stranger’s presence he was thankful for: the wave produced collateral damage so powerful that it sliced asunder tendrils in the mangrove, reducing the density tenfold.

As a parting gift, they also provided a plastic cup, less than half the length of his bony fingers.

“Do not drink a full cup of water, okay? Suck on the ice. Sip the contents. Otherwise, it will sting, and we will have to attend to you again,” they said.

“What do I do? The water isn’t froze—” The boy’s voice croaked and cut-off. He had not the strength nor the mental clarity to finish his own broken speech, let alone ask pertinent questions.

Once the men and women had departed, he placed the plastic lifeline on tiles just outside the windowsill. He avoided eye contact. Reluctantly followed the confusing rules. But as if by divine design, the clouds soon froze a sundry grey overnight and frozen flakes hardened the seas. The cold saturated the deepest crevices of the olive bricks, and by proxy, what few droplets of water were afforded to him turned into ice cubes. They would melt slowly.

And so, he decided to play a game with these inhospitable visitors.

If time was a factor in the melting of ice, he would simply wait as the tendrils did. But that necessitated a mind of patience, of which boredom currently occupied. He paced and moved about for hours, as the ice seemed to respond to his gaze and slowed its natural process out of spite. The boy would come back late at night to check; his thirst was a constant companion.

Morning arrived. Mere minutes before the visitors were scheduled to dock, he peeked at the glass and behold, a full glass of water was ready to drink. He scoffed it down with little care for the taste.

The visitors boarded his isle and did their regular checks and upkeep: changing the weather-beaten tarp that covered a patch of missing rooftiles, feeding soupy food into the pulsating vines and transplanting new residue into powdery mortar cracks. They repaired a portion of the second level too, yet he was not awake to remember it. A fragment of time had been carved out by bright lights and brighter visions of masked men with scary utensils.

Like a farm animal, his body had been prodded and poked. At the end of the inspection, two of the visitors exchanged glances with each other, eyes betraying a grimace devoid of hope. The attic trembled.

What did they see?

Would it keep him here forever?

“Did you sip the water we gave you?” They asked, shuffling between curtains in his cramped room. It was an amusing question for the boy, since he did the legwork of retrieving the liquids. Why should he let these people dictate his actions?

He replied, chewing his thumb. “Yes.”

Placating them was still his best course of action. Last time he refused their warnings, his stay was marred by more frequent memory wipes. They would arrive; he would forget.

The boy returned to solitude once they made their peace with his state. He scrambled up the tiling to his favourite lookout: two sloping edges met at a deltoid junction on the third level. From that spot, every angle of his surroundings flared out under a golden sun. He took a glance at the far left and right fields of vision, which was not something he tended to do—his parents only ever came from the one direction. Little dots of fluorescent light bounced off the rippling currents of midday fog that settled around his isle. They were the same colour as his house, and he liked to imagine the existence of other isles, other boys and girls sharing the same struggles.

The thought, however true or untrue, provided some comfort.

That night, he rested into his pillow with a cheeky grin plastered on his pallid skin; he had won a small victory again over the nurses and doctors in the Cancer Ward of the Royal Children’s Hospital.

✷

Christopher Todaro is an Australian author writing fantasy, sci-fi and literary fiction. With a personal history of Leukemia, he tackles diverse themes of mortality, medical trauma, isolation, and identity. With his first publication, he hopes to bring his keen sense of introspection to the fantasies and ideas he dreamt of exploring in the hospital.